I recently made the decision to step away from coaching. It wasn’t an easy decision to make. I have loved skating, and loved coaching for as long as I can remember. I love everything about being on the ice with my athletes, interacting with them, guiding them, planning their training, reassuring them when needed, and laughing with them.

The simple fact is, I got TIRED. I will write more on WHY I stepped away and how I felt after I made the decision in another blog. In this one, I want to pay my respects to the many amazing coaches I have had the opportunity to work with.

I have been incredibly lucky to practice my craft alongside some of the best coaches in the world; coaches who care, and go the extra mile for their students, time and time again. Coaches who have inspired me, challenged me, and taught me so very much. So as I step away from the world of coaching, I wanted to say a thank-you to all my fellow coaches.

So, here’s to the coaches who give everything so that their skaters can succeed.

Here’s to that first coach that carried us onto the ice on our first day of skating; drying our tears, wiping our noses, and picking us up over and over and over until we could, finally, get up by ourselves and stand on our own.

Here’s to the coach that helped us develop our abilities from the very beginning, often for years, giving us the foundation we needed to excel later in our career, until we decided it was time to move on and had to say good-bye.

Here’s to the coach who gave us that last bit of finesse, polish, and competitive push we needed to succeed at the highest levels of competition.

Here’s to the coaches who found us a dress for our first competition when our mom forgot.

Here’s to the coaches who lectured us on taking responsibility for packing our own skate bag, tying our own skates and bringing our own water bottle, even while re-tying our skates EVERY session for us until our fingers could FINALLY tie them on their own.

Here’s to the coaches who spent countless hours finding program music, cutting said music, (12 hours or more for one cut, amiright?) finding or designing the perfect costume, and then, as if that wasn’t ENOUGH…. choreographing those programs.

Here’s to the coaches who pick up students and take them to and from the rink, even though they know they shouldn’t, and are making themselves legally liable if anything happens during that drive, but if they don’t, their skater won’t be able to participate in the sport they love.

Here’s to the coaches who find a second job, so they can afford to coach when the hours they get at their small club just won’t cut it.

Here’s to the coaches who find a second job so they can afford to coach when the small club they work for refuses to pay them what they are worth. (You ALL know it happens.)

Here’s to the coaches who place their skaters over their own children and family, re-scheduling family vacations, weekend get-a-ways (Ha! WHAT weekend get-a-ways?) and after-school activities to accommodate their athletes’ skating schedule.

Here’s to the coaches who risk their marriages because their spouses don’t understand the stress of coaching and are tired of hearing us complain about work.

Here’s to the coaches who teach in small clubs, yet somehow manage to find the off-ice programs, extra-ice, and equipment needed to help their skaters succeed even when the skaters themselves can’t afford it.

Here’s to the coaches at large clubs who deal with competitive pressures every day and manage to navigate political waters like champs.

Here’s to the coaches who feel like if they EVER see another hotel room again it will be too soon.

Here’s to the coaches who desperately need that glass of wine to take the edge off after standing for 14 hours on the cold concrete at a competition and taking an emotional ride with EVERY student.

SKATING PARENTS. Enough said.

Here’s to the coaches who spend more than they can afford on books, seminars and courses to give their very best to their clients.

Here’s to the coaches who stay awake at nights worrying and wondering why they just can’t get their skater to LAND. THAT. DOUBLE AXEL!

Here’s to the coaches who don’t let the politics get them down; who stick to the plan and trust their instincts and their athletes.

Here’s to the coaches who know when it’s time to move on and provide support and encouragement through-out all phases of a skater’s career.

Here’s to coaches that know that while their time with an athlete may be small, their impact is great, and strive to be the best influence they can be.

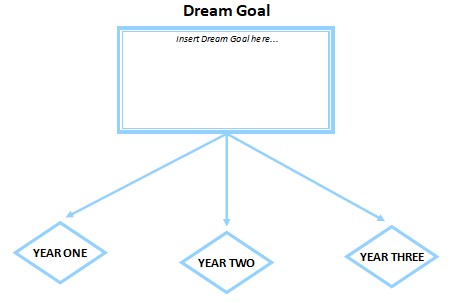

Here’s to the coaches who spend hours and hours pouring over technical announcements and strategizing program content to make sure they give their skaters the best chance they can during a competition.

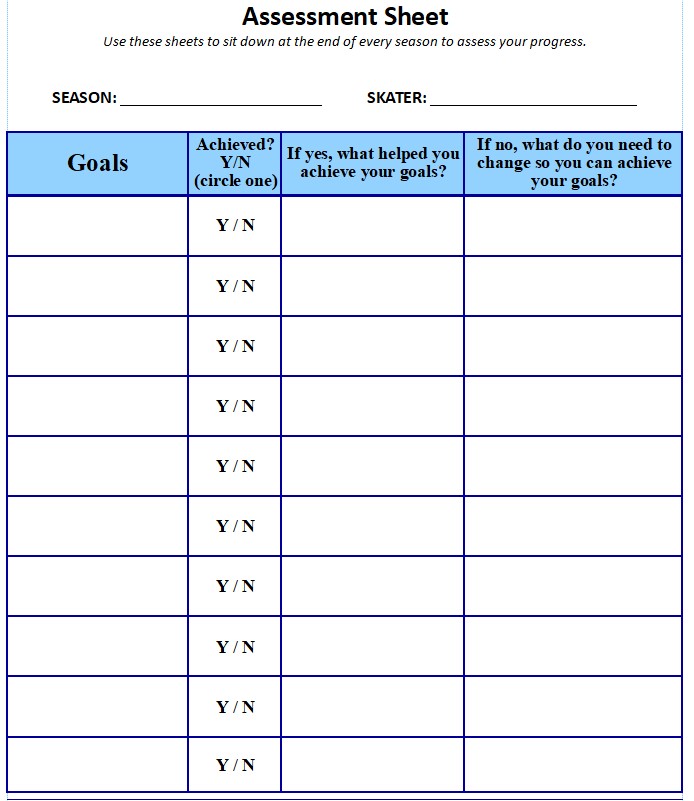

Here’s to the coaches who lessen the sting of defeat by bolstering confidence and emphasizing the lessons learned from failure.

Here’s to the coaches who teach winning with grace and dignity, and set THAT example EVERY. SINGLE. DAY. for their skaters.

Here’s to you coach, WE SEE YOU.

Got any stories you want to share about how your coaches inspired you? Any funny coaching stories? Share with the class in the comments below. While you’re at it, do me a favor, and share this with your friends!