This blog is a tag-team effort between me and AI—think of it as my over-caffeinated intern who spits out ideas while I handle the heavy lifting. I research, fact-check, edit, and fine-tune everything to make sure it sounds like me (not a robot with a thesaurus). AI helps with the grunt work, but the heart, style, and final say? That’s all me, baby.

I want to tell a story about what happened to my daughter and me in the Canadian healthcare system, because I know we’re not alone. I’ve changed all the names for anonymity, but the story is, sadly, all too real.

The Pediatrician We Trusted…At First

Years ago, I was referred to a pediatrician for my daughter Ava. At the time, she was around six and suffering from chronic stomach pain, constipation, recurring croup, and constant anxiety related to school.

She had nightmares, meltdowns, and was being ostracized and bullied. I knew something deeper was going on. I didn’t have the words “autism” or “ADHD” yet, but my mom gut told me she was different—and struggling.

Our pediatrician—we’ll call him Dr. McLecturepants—was very knowledgeable. Ava liked him. He was good at addressing her physical health issues. He took things seriously, referred us to specialists, and was often thorough.

But there were red flags.

Dismissed, Doubted, and Lectured

Early on, I was struggling to get Ava to take medication. What I now know is ARFID, sensory aversion, and autistic rigidity was, back then, just a nightmare every time I had to administer meds.

Meltdowns, sobbing, trauma for both of us.

When I asked for help, he didn’t offer compassion. He gave me a five-minute lecture on how I needed to “take control” and “stop letting her run the show.” It was humiliating. I left feeling like a failure.

From then on, I was nervous around him. I often wondered, would he speak to me this way if a man were in the room? I was a single mom. White. Tired. Not wealthy. He was a male doctor with a strong accent—possibly Middle Eastern—and although I didn’t want to bring culture or bias into it, I couldn’t ignore the power dynamic.

I wrestled with myself for even thinking that cultural background might play a role — not because I wanted to stereotype him, but because I’ve lived long enough to know that gender dynamics can be shaped by upbringing, culture, and society. Still, I sat with the discomfort of that thought and tried to focus on what I knew: I felt talked down to, and I didn’t feel respected.”

I felt small.

Like I was being treated as a hysterical mom, not a capable one.

Homeschooling: The Best Decision We Made

When school became unbearable for my daughter, I started researching homeschooling options. It wasn’t a knee-jerk decision. I consulted experts (including a clinical psychologist), read studies, and made spreadsheets. I also began compiling information about ADHD and neurodivergence, trying to be prepared to make my case.

Dr. McLecturepants dismissed homeschooling outright. Didn’t want to hear about the trauma Ava was experiencing. Didn’t care that her nightmares and pain disappeared within two weeks of being pulled from school.

He continued to disapprove, even when I brought up ADHD. That, at least, he was more receptive to, but the lectures didn’t stop. I kept going back because he was knowledgeable about ADHD, and I thought I needed that.

Rather, I thought my daughter needed that, and I should just shut up and deal.

The Diagnosis Battle

But when I brought up autism? He shut it down. Said she couldn’t be autistic because she made eye contact. (Yes, really. Hello, 1955 called and they want their scrubs back)

Eventually, I demanded a referral. I gave him research. I asked for a specific autism specialist recommended by a trusted friend.

McLecturepants reluctantly referred us, but warned me the doctor “diagnosed everyone” and other professionals didn’t like him. I couldn’t believe he was dragging me into some petty professional rivalry when my daughter’s health was on the line.

The diagnosing doctor met with my daughter, gave a comprehensive evaluation, and said, “Yes. She’s autistic.”

I went through ALL the feelings that day—IYKYK—but one of the ones I never expected to feel was validation. Someone else finally listened to me and I wasn’t crazy, which is what my pediatrician had been making me feel like.

The specialist did say kiddo might not have ADHD, but I trusted my gut—because comorbidity is common, and I’d done the reading. I was more worried that McLecturepants would react poorly when he read the report, particularly the part about the specialist disagreeing with his diagnosis.

It’s not fun to feel you’re caught in a pissing match between two health “professionals,” which only magnified my feelings of “walking on eggshells” with McLecturepants.

The Funding Form Fiasco

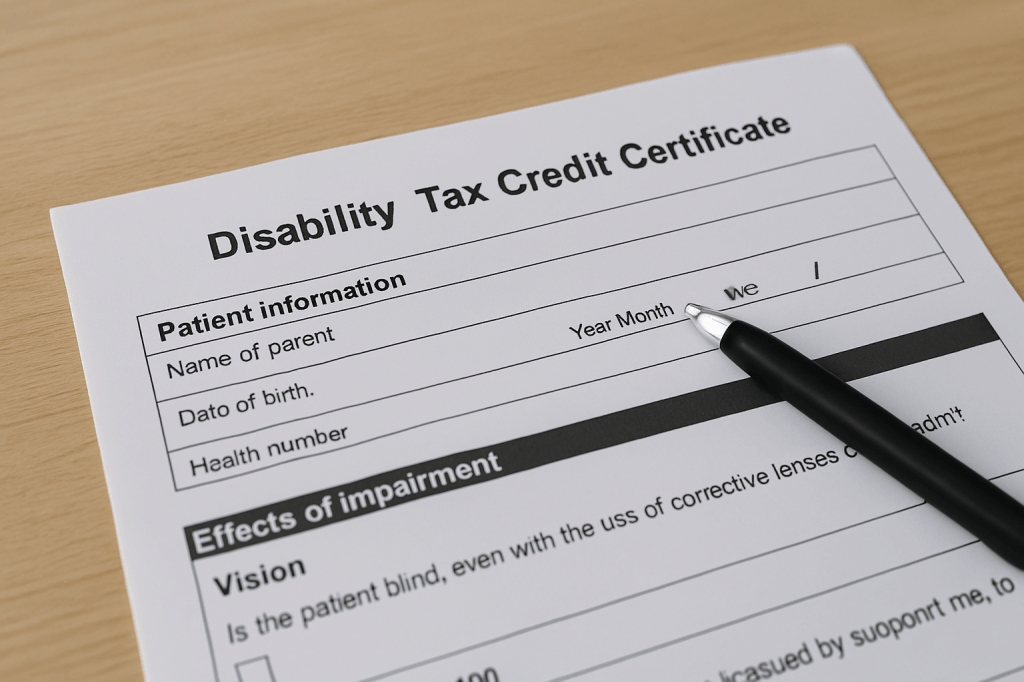

Fast forward. The Disability Tax Credit needed renewing. We’d been working with a phenomenal ASD counsellor who’d seen Ava regularly and knew the extent of her challenges. The DTC forms went to Dr. McLecturepants. I was told it would take months to fill them out.

I got emotional. After all, it was our only funding, given we’ve been on waiting lists for years with the Ontario Autism Program and Special Services at Home. (I’m looking directly at you, Doug Ford).

McLecturepants ended up filling them out quickly over the holidays, which I appreciated—until I read them. He’d minimized kiddo’s struggles. Downplayed how much support she needs. Even checked the box saying her deficits would likely improve over time—as if autism isn’t a lifelong neurotype.

When I first read what the pediatrician had written, I questioned everything about my reality. Maybe it wasn’t that bad? Maybe I was exaggerating, and making too much out of our struggles. Maybe there was something wrong with ME that I couldn’t handle the extra work required for my daughter?

Thankfully our counsellor, who at this point had been visiting with my daughter and I for over a year, twice monthly for an hour at a time, also expressed her shock and surprise at how inaccurately Dr. McLecturepants had characterized our daily struggles.

I was heartbroken. I drafted a letter—respectful, clear, and shared with our counsellor and friends for feedback. After all, I didn’t want to provoke another lecture. I didn’t want to make things worse, or insult our pediatrician’s professionalism, or god forbid, challenge him or hurt his ego.

I brought in observations from myself, her grandparents, coaches, teachers—any adult in Ava’s life. I asked him to reconsider.

He refused. Told his receptionist he wouldn’t change it. So I made an appointment.

Enough is Enough

This time, the gloves were off, and I knew the advocate (me) needed an advocate.

So I brought my mom—who never takes my side in these things; after all, I’m too outspoken, too sensitive, too…(you get the drift).

But this time she came, because I needed backup. It meant so much to me that she did that, even though I could see she didn’t believe it was as bad as I said it was.

When we tried to explain, he talked over us.

Not once, not twice.

Repeatedly.

McLecturepants wouldn’t acknowledge the fact that we might have a better understanding of the difficulties my daughter has every day. My mom—stoic, practical, no-nonsense—who never speaks up and hates confrontation, actually shouted: “You’re not listening to her!” after he cut me off yet again.

That’s when I stood up and said: “We’re done. You’ve lectured me for years. Dismissed me. Put me in the middle of conflicts with other doctors. I believe you’ve treated me differently because I’m a woman, and I don’t feel safe bringing my daughter here anymore.”

We left.

One Final Violation

I picked up kiddo’s files a week later. On my way to our counsellor’s office, I noticed something strange. Mixed into Ava’s files were records for another child. Operations, procedures—stuff my daughter had never had. A huge privacy breach. I returned them immediately, because that’s what I’d want another parent to do if it were my child’s info.

But wow.

Just wow.

This from the office of a doctor who’d been lecturing me for years about MY incompetence as a mom?

Blacklisted for Speaking Up

We’ve been seeing our GP ever since. Lately, I’ve been researching other possible underlying conditions—things like hypermobility, POTS, immune dysfunction—and brought them up with our GP, who was amazing and agreed to help. He referred us to another pediatrician in our town.

I didn’t realize this pediatrician was at the same office as Dr. McLecturepants. You can imagine the surprise when their office called to schedule the appointment. Still, I knew I would have a longer wait for a pediatrician from other, larger centers, so I agreed to the appointment.

Why would I go back?

If you’ve ever had a sick child, you’ll understand that all you care about is making their quality of life better.

And then, today, after picking up my daughter from school, a call came in from our GP’s office, which I took over our hands free, thinking it was about my upcoming blood tests.

We’d been rejected. Well, technically the word they used is, he has “declined.”

The new doctor wouldn’t take us as patients because of my “issue” with the previous pediatrician. And my daughter heard every word of that rejection.

The message was clear: they stick together.

This is what it’s like to advocate for a neurodivergent child in the medical system as a single mom.

No one’s listening.

Backing it Up: What the Research Says

Sexism in the Medical Profession:

- A 2022 study published on “Women’s Experiences of Health-Related Communicative Disenfranchisement,” found that women are more likely to report feeling dismissed, not believed, or condescended to by medical professionals.

- Female patients, especially mothers, often get labeled as “anxious” or “overreacting” when advocating for their children, leading to delayed diagnoses and interventions.

Bias Against Single Mothers:

- Single mothers are statistically more likely to be perceived as less competent parents by both professionals and the public.

- These biases can lead to increased scrutiny, less support, and more judgment in medical and educational settings.

Challenges of Advocating for Autistic Children:

- Parents often report having to fight for recognition of their child’s needs, with many diagnoses being delayed due to outdated stereotypes like “they make eye contact.”

- Autistic girls and children with Level 1 Autism (formerly known as Asperger’s) are often underdiagnosed due to masking and lack of understanding by professionals.

Privacy and Confidentiality in Canada (PHIPA):

- The Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) mandates that healthcare providers protect the confidentiality of all patient information.

- Sharing or misfiling another child’s medical information, even accidentally, is a breach under this act and can be reported to the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario.

Medical Ethics & Gatekeeping:

- Physicians are ethically bound to advocate for patient welfare and make decisions free from personal bias or inter-professional politics.

- Refusing care to a child based on a parent’s disagreement with another doctor raises serious ethical concerns about bias, access to care, and professional conduct.

Why Parents Shouldn’t Be Penalized for Speaking Up:

- Advocacy is not aggression. Speaking up about misdiagnosis, misrepresentation, or mistreatment should never result in being blacklisted.

- Punishing parents for advocating silences necessary voices and puts children’s care at risk.

This is my story. It’s also the story of so many parents out there who’ve been dismissed, condescended to, or penalized for doing what they’re supposed to do: protect and advocate for their child.

We shouldn’t have to shout to be heard. But sometimes we do. And when we do? We deserve to be listened to.

April is World Autism month. Do your part. Speak up. Advocate. Scream. Pound your fists. Or better yet, write a blog and call the assholes out.