Last weekend my daughter danced in her studio’s end-of-the-year recital. The show was a success, full of the usual suspects; seasoned performers hip-hopping their way to fame, teeny-weenies out for their dance debut loaded with sparkles and wide-eyed anticipation, and budding street dancers learning the breakdance ropes.

While all of these regular recital occurrences are heart-warming, what got me in the “feels” was that I got to watch the entire thing from the audience.

This may sound odd, given that my little dancer is not so little anymore. In fact, at nearly twelve, she’s taller than most grown women. And you’re likely now thinking that I’m a total helicopter mom, hovering like there’s no tomorrow, too afraid to cut the apron strings and let my daughter look after herself.

While that may be true, there’s also another factor to consider. You see, my daughter is neurodivergent; she has ADHD and is on the autism spectrum. This means that she is quirky, beautiful and (in my humble opinion) fucking brilliant.

It also means she has significant challenges in places and at events that you and your neurotypical kiddos likely take for granted.

I won’t ever take something like watching a dance recital from the audience for granted again. I’ll tell you why.

Source: Unsplash

The Extra Steps of Autism

My daughter doesn’t look any different than your average tween. Given that she is considered Level 1 ASD (formerly known as Aspergers), nothing would cue you that she is any different from a neurotypical child.

This is why so many parents of kids on the spectrum get the side-eye, eye-rolls, and just about any other eye-related behaviour from other parents, teachers, doctors, etc.

No two children on the spectrum are the same, but let me share with you some of the challenges my daughter has had to overcome in her dance career.

Motor Difficulties

You know how kids can effortlessly tie their shoes or change outfits like they’re in a backstage dressing room of a Broadway show? Well, that’s not exactly a walk in the park for my kiddo.

With her motor skills functioning a little differently, quickly tying tap shoes or changing sparkly leotards might as well be an Olympic event. And let’s not forget the actual dance numbers.

With balance and coordination playing a cheeky game of hide-and-seek, the challenge of mastering those intricate steps is on another level.

Issues with Working Memory

Ever tried to keep track of multiple dance numbers, their order, and the steps for each in your head? My daughter tackles this challenge head-on every time she steps onto that stage.

Prioritizing tasks and decision-making are like trying to solve a Rubik’s cube blindfolded. The struggle with working memory is real y’all.

Executive Function Challenges

Imagine having a long list of instructions, each more complex than the last. Sound overwhelming? Now, think about how it feels when every day is filled with these lists and not having a freaking clue where to begin or how to put the required steps in order?

That’s the reality for children like my daughter. Delayed executive function development is like trying to solve a jigsaw puzzle with missing pieces. Is it any wonder they get frustrated and lose their shit?

Emotional Dysregulation

Feelings for my daughter are like waves during a storm, overwhelming and unpredictable. Her emotions are big, bold, and often challenging to rein in. It’s like riding a roller coaster without a safety bar, thrilling but also a little scary.

The hardest part as her parent is to watch the shame and guilt play across her features once she has calmed down and realized what she said and did while she was struggling for control.

Even though my kiddo is starting to realize that when she gets overwhelmed, her frontal lobe is not in control, and she is in the clutches of her amygdala and the dreaded fight/flight/freeze/fawn (although there is a strong argument for using “feign” instead of fawn) response cycle, she still feels bad about her behaviour after the fact.

Sensory Sensitivities

Imagine being at a rock concert, but the music’s too loud, the lights are too bright, and the crowd’s too much. Now, try picturing that every time you’re in a room full of kids or under fluorescent lighting.

That’s what my daughter deals with — a world where sounds, smells, and sights can be as piercing as a siren’s call. Because she perceives the world differently and often more intensely, she can experience these sensations as discomfort and even pain.

Now see yourself at a dance competition or recital, packed together in a dressing room with hundreds of other dancers, all anxious and excited. The steady drum of chatter, shouting, crying, and music would be enough to drive a neurotypical person to drink, let alone someone who’s conditioned to perceive these stimuli as threats! (To clarify, I don’t let my daughter drink…so don’t come for me!)

Problems Reading Social Cues

Reading social cues for my daughter is like deciphering hieroglyphics without a Rosetta Stone. It’s tough not knowing how to fit into the social puzzle, feeling isolated in a room full of chattering children.

But thank the goddess for our dance studio. Through careful attention to fostering a climate and culture of family and inclusion, they have helped my daughter fit in every step of the way. I wish I could say the same for our previous studio, but that’s another story for another time. (And perhaps that aforementioned drink)

Triumph in the Dressing Room

Usually, I am my daughter’s special assistant in the dressing room. My job is to make sure she can navigate quick changes, take a sensory break if necessary, calm her in case of overwhelming nervousness to prevent meltdowns and help her navigate the environment and pressure around her.

I always ask my kiddo if she wants me there with her in the dressing room or if she’d like to try it on her own, as I’m trying to foster independence and push her boundaries, but I want her to feel ready for it.

So I wasn’t surprised when she asked me to be her special dressing room assistant once again.

I don’t mind this, but the fact is, it is usually only my daughter and me at these events. So when I’m below in a dressing room, I am not in the audience to hoot, holler, yell, and clap for her when she’s onstage. And that means she has no one in the audience to do that for her.

As you can imagine, for an only child who seldom sees her father and sees ALL the other families full of siblings and relatives attending, this is hard for both of us.

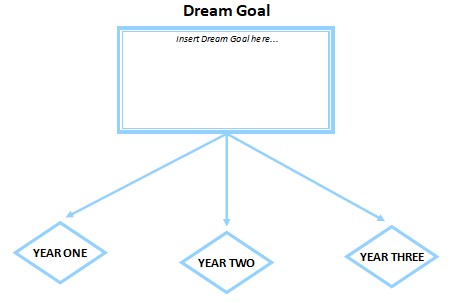

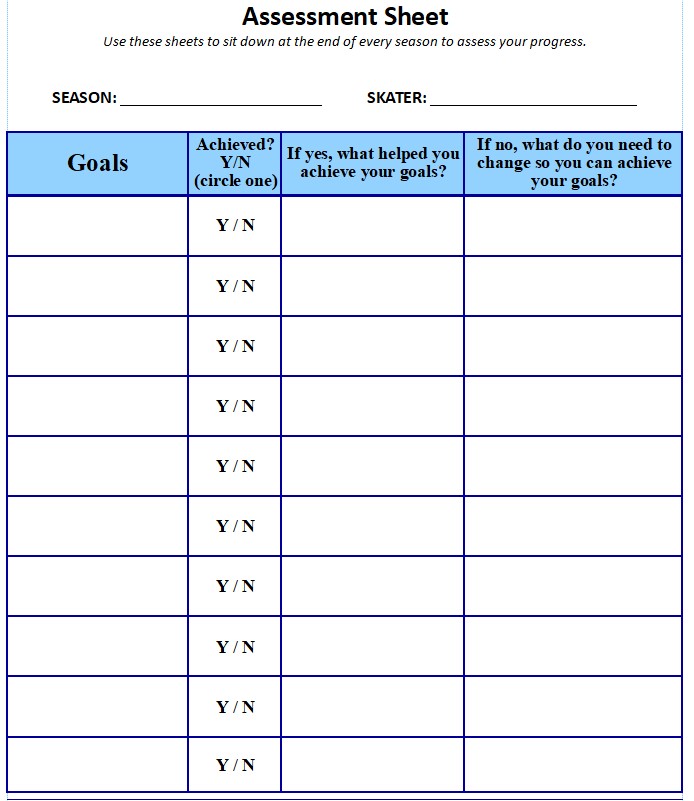

Still, I was prepared. I’d created extra lists for my l’il dancer with the order of her numbers, all carefully highlighted. I’d labelled each of her dance bags carefully, even crafting numbers to hang on each hanger so it would be easier to see which one was next.

I’d done all the things necessary to ensure a seamless experience. I’d packed all my kiddo’s sensory stuff, like headphones, earbuds, fidget spinners, a tablet and a charger, not to mention a cell phone. You name it; we were ready.

Then, suddenly, as we were setting her bag up in her designated space, my daughter shot me an “I’m so embarrassed my mom is here look” and started shooing me away.

I have to admit. I froze, unsure if I was actually seeing what I thought I was.

Sure enough, my daughter wanted me to leave her alone so she could hang with her dance friends. When I asked if she could handle the quick changes, she said she could, and I should leave her alone.

Source: Pexels

A New Perspective: Joining the Audience

I just about cried. Partly, if I’m being honest, because this was a huge hurdle, and it meant my baby was growing up, which is difficult for every mama bear, neurodivergent or neurotypical alike.

But partly because of the overwhelming sense of relief and freedom to sit and enjoy myself at a function. Whether it was a family dinner, a holiday gathering, a school assembly, or a dance recital, I had yet been unable to do this.

I don’t think you can understand how it feels to always be alone when you’re the parent of a kiddo on the spectrum. Because your child is more, needs more, and demands more, you have to give more, be available more, be more organized, be more prepared, be more calm…I think you get the picture.

This sense of being an uber parent is not conducive to sitting and having a cocktail at a dinner party, socializing with family at a Christmas get-together, or watching your daughter shine onstage at dance recitals.

Until last week.

And shine, she did. Although it was hard to see from the tears in my eyes. (I’m not crying, you’re crying)

Parenting on the Spectrum Means You Celebrate the Ordinary Moments as if They Were Extraordinary

My daughter did it on her own, and I couldn’t be prouder. You see, for parents like me, we don’t just celebrate the recitals or awards. We celebrate the moments when our children prove to the world, and more importantly to themselves, that they are so much more than a label.

We celebrate when they show their strength and resilience in the face of adversity and face the challenges of a world that can be overwhelmingly stacked against them.

So yes, I won’t ever take something like watching a dance recital from the audience for granted again. Not because it’s a luxury but because it’s a testament to the beautiful, quirky, brilliant girl my daughter has become. And how damn proud I am of her.

If you want to share some ordinary yet extraordinary moments with your neurodivergent child, comment below, and follow me for more blogs!

Better yet, why not check out my online store, BellaZinga (inspired by my daughter and her neverending one-liners) for some merch with a side of neurodivergent sass? While you’re there, you can download my eBook “Friends Beyond Differences: Embracing Neurodiversity.”

It’s an engaging guide written specifically for neurotypical kids aged 6-12 to help them understand and embrace their neurodiverse peers.

And remember, our differences make us unique, but our humanity binds us together. Let’s ensure every child, regardless of their neurotype, feels accepted, loved, and capable of dancing their own unique rhythm.

Shine on, my beautiful neurodiverse kiddos.

Shine on.